In the Collision Model we mentioned that the collision shapes are rasterized (in the original game) in order to evaluatate the terrain collisions. But how are we going to do this, in the day and age of GPUs?

CPU sampling

The first approach I tried was to pick a few points inside each quad of a collision shape, calling them “samples”, and perform the terrain collision and averaging on them, as if they would approximate the result of fully-rasterized surface. The samples were computed by tessellating the quad and picking the centers of the sub-quads:

Even having a single sample at the center of each collision quad produces acceptable results for physics simulation. However, it is not sensitive to intersections with tiny and sharps pieces of the terrain.

GPU pipeline

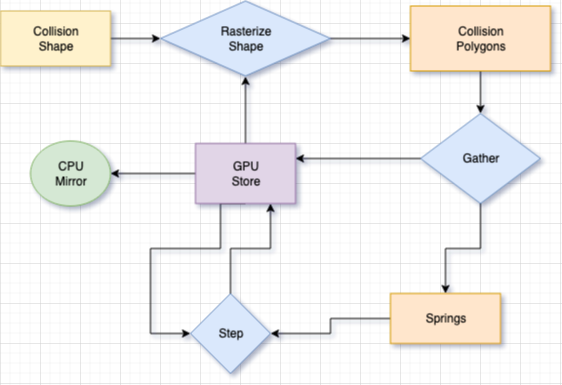

Alright, so how about using the only rasterization hardware we have today? Vange-rs features a fully closed GPU physics simulation loop:

The core data piece of the puzzle is the GPU store, which is managing a buffer full of persistently updated structures:

struct Body {

// external parameters, such as user controls

vec4 control;

// persistent state

vec4 engine;

vec4 pos_scale;

vec4 orientation;

vec4 v_linear;

vec4 v_angular;

// temporaries

vec4 springs;

// constants

Model model;

Physics physics;

vec4 wheels[MAX_WHEELS];

};

CPU-side keeps an association between the objects in the world and entries in the GPU store. It also schedules updates (via buffer-to-buffer copies) onto some of the fields from time to time, for example when a new entry is initialized.

Shape rasterization

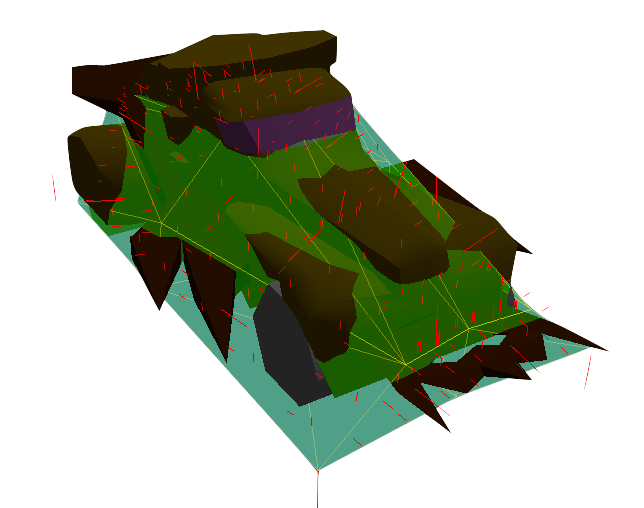

This is a graphics rendering step that is done on a per-object basis. We render the collision shape quads by transforming them into world space, and for each pixel sampling the terrain and computing the penetration depth:

If the collision is detected, it’s parameters are added atomically to values in a separate buffer, representing a sum of all the effects on it from the rasterized pixels, per shape polygon. Atomic operation is needed because we have multiple pixel shaders reading and writing to the per-polygon data cell. This requires data to be integer, and we end up encoding both the count and the depth into the same value:

uint encode_depth(float depth) {

// notice the "1U" here added to the higher bits as the count bump

return min(uint(depth), DEPTH_MAX) + (1U<<DEPTH_BITS);

}

float resolve_depth(uint depth) {

uint count = depth >> DEPTH_BITS;

return count != 0U ? (depth & ((1U << DEPTH_BITS) - 1U)) / float(count) : 0.0;

}

Interestingly, since the atomic operations on a storage buffer are the only side effects of our pixel shaders, the render pass doesn’t need any attachments! This is a rare example of a graphics pipeline that needs rasterization but doesn’t output any pixels.

Note: there are much better ways of gathering data on GPU than relying on atomics, I just picked the simplest one.

Contact resolution

At this stage, we have a buffer with collision info for every quad of every object on the level. We need to derive the spring forces from it. We do this by running a compute job, which has a thread per game object. One needs to be careful with extra threads coming from the thread groups: we either need to make them do nothing, or make sure that the source and destination buffers have enough space for them to work on, even if we don’t care about the results.

Each thread is supplied with a range of addresses into the polygon buffer, based on what shape quads belong to the object. It iterates the polygon data and resolves the contact point and velocity. A thread produces a contribution to the string force affecting the object, as well as changes the velocities based on the impulse of the collision, as described in the Collision Model:

for collision_poly in collision_polygons {

let contact_point = match resolve_contact(contact_poly) {

Some(contact) => contact,

None => continue,

};

let collision_direction = vec3(0, 0, -1);

let impulse = evaluate_impulse(contact_point, collision_direction);

body.v_linear += impulse;

body.v_angular += jacobian_inv * cross(contact_point, impulse);

apply_spring_force(contact_point, collision_direction);

}

Technically, the spring force output is a separate temporary piece of data, but currently we store it just as a part of the struct Body. Every processing step on the GPU accesses the GPU store and messes with some of the fields.

Simulation step

The rest of the simulation logic is contained in a big fat compute job doing a step. It, once again, launches a thread per game object. The logic of a thread is straightforward but heavy on computation:

- apply player controls to the engine parameters

- process the impulses from the moving wheels

- process the gravity and spring forces

- apply the drag force

- update position and orientation

This is largely the same logic as we have on the CPU path, just operating on fields of our main storage buffer. wgpu-rs makes sure the effects of these updates are visible to consequent compute and rendering jobs, taking care of the synchronization.

The whole loop is done multiple times per frame, based on the configurable maximum delta time. This ensures the stability of the simulation equations. On slower GPUs, we may end up in a situation where the GPU just can’t keep up with the work, given that the longer it takes, the more iterations it would be asked to do.

Readback

This is all cool, but what if we need to know the actual position of an object on CPU at any point? For example, for AI decision making, unless that part goes on the GPU in the future as well :)

Every frame, we request a copy of the positional data into a separate buffer. Once this copy is done on the GPU, we map this buffer on CPU, read the data, and update the CPU-mirror of the affected objects. Since there are multiple frames in flight, these download buffers need to be ring-buffered. wgpu-rs takes responsibility of deferring the actual mapping of the contents to a point where the buffers are no longer used by the GPU.