About a year ago we described a method of “true” 3D rendering, called Bar Painting. A number of clever optimizations followed, but the nature of the method remained to be very brute-force. It was still too inefficient for real time.

Today, we have a new rendering method implemented, evolved from the original ray-tracing algorithm. The major improvement is an acceleration structure: we use a voxel octree to skip large distances known to have no terrain present in them.

Algorithm

The main problem of the original ray-tracing was that it was way too easy to miss a ray occluder. Whatever the step is, any terrain feature in size less than the step will potentially be missed. Therefore, we want to be able to answer a simple question: is there anything in the given sub-volume?

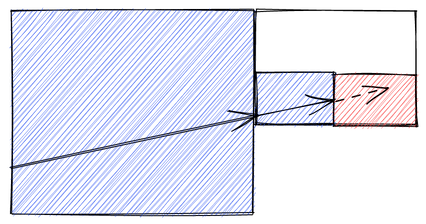

One of the easiest ways to split a volume is by doing it in half along each axis. This hierarchy forms a volume octree:

What we want is to jump from one border of a voxel straight to the opposite if we know that the voxel doesn’t have anything in it. And the bigger the voxel we choose (i.e. based on the hierarchy level of the octree) - the better. This guiding principle makes the core of the algorithm:

- Find out what voxel the current point is in. Check its occupancy.

- If empty, traverse to the opposite side of the voxel, continue with the voxel behind the border. If this border is also a border for the container voxel - consider the container first.

- If occupied, go deeper and consider the sub-voxel we are in.

- If we reach the smallest voxel level (leaf of the octree), ray march through the voxel with a fixed step.

The devil is in details, and also - in the implementation. Getting these bits of logic right, also taking care of the edge cases (e.g. we are hitting a corner of the voxel), is most challenging with this task.

Storage

Ideally, the smallest voxel is 1x1x1 in size. This would make ray-marching in (4) unnecessary, but it can take quite a bit of memory. A full level in the game is roughly 2048x16384x256, which would be 8 giga-voxels. And we are talking about a game from 25 years ago! Therefore, we can settle on a bigger voxel, say 1x4x1.

Next question, how do we store voxels? The octree hierarchy is similar to mipmapping, so it’s natural to just store the occupancy in a texture. There is a problem - the smallest texture format supporting storage access is 32-bit. And we only need 1 bit…

Let’s just store it in a buffer then. We can use bit operations to insert/extract the bits, which are tightly packed. One downside of a naive buffer layout is that texels that are together are often not nearby in memory. There is a clever trick to solve that - Morton coding. This is what GPU does internally to our textures, so we’ll want to do it manually to our buffer.

Code we used was taken from the ryg blog and ported to WGSL:

// "Insert" two 0 bits after each of the 10 low bits of x

fn morton_part_1by2(arg: u32) -> u32 {

var x = arg & 0x000003ffu; // x = ---- ---- ---- ---- ---- --98 7654 3210

x = (x ^ (x << 16u)) & 0xff0000ffu; // x = ---- --98 ---- ---- ---- ---- 7654 3210

x = (x ^ (x << 8u)) & 0x0300f00fu; // x = ---- --98 ---- ---- 7654 ---- ---- 3210

x = (x ^ (x << 4u)) & 0x030c30c3u; // x = ---- --98 ---- 76-- --54 ---- 32-- --10

x = (x ^ (x << 2u)) & 0x09249249u; // x = ---- 9--8 --7- -6-- 5--4 --3- -2-- 1--0

return x;

}

fn encode_morton3(v: vec3<u32>) -> u32 {

return (morton_part_1by2(v.z) << 2u) + (morton_part_1by2(v.y) << 1u) + morton_part_1by2(v.x);

}

Interestingly, we’ll never need the reverse transform. The only way we go is from a 3D coordinate to the linear index.

There is a nuance to this encoding though - it’s made for cubic volumes. Our volume isn’t a cube, and so we’ll first need to tile it, and then use Morton codes to index bits inside each of the tiles. We used 8x8x8 sized tiles, each having occupancy encoded in 64 bytes.

So, all we have the following data composition:

- world split into voxels of size 1x4x1

- voxel grid has hierarchy, we stop at level 8

- each level is split into 8x8x8 tiles

- each voxel within a tile is assigned a single bit

Preparation

How do we actually fill up the occupancy acceleration structure? There are many ways possible, and we tried some of them. For the base hierarchy level, we assign each compute invocation a 2D coordinate. This allows us to only fetch the initial data once. An invocation goes through the Z axis twice: once to zero out the contents, and once to fill up the space being occupied.

Two things are important here. One - is to use the occupancy buffer atomically:

struct VoxelData {

lod_count: vec4<u32>,

lods: array<VoxelLod, 16>,

occupancy: array<atomic<u32>>,

}

@group(0) @binding(0) var<storage, read_write> b_VoxelGrid: VoxelData;

We want to flip individual bits and guarantee the independence of the operations. Interestingly, the same buffer can be used in drawing as non-atomic.

The other important thing is to separate clearing from setting by having a workgroupBarrier. Regardless of whether atomics are used or not, we want to ensure that each workgroup only works on separate set of data, and no invocation starts putting the occupancy bits in before they are reset.

When the base level is done, we want to descend into higher levels, filling one at a time. Note that we can’t fill all of them at once in a single dispatch because WebGPU doesn’t have a global barrier available.

We organized our code to have one invocation responsible for a single voxel (represented by a bit). It scans 8 child voxels and sets its value on the destination. This doesn’t need a dedicated clearing step.

Overall, data preparation is a huge piece of work for GPU to chew at once. We’ve seen DX12 implementation resetting the driver with Timeout Detection and Recovery (TDR). It’s not the best experience at the start even when it works, either, since everything is frozen while this job is running. For this reason, we process the terrain in chunks, up to a million compute invocations per frame.

Fetch code

When doing the main traversal, getting a bit of occupancy is done with this function:

struct VoxelLod {

dim: vec3<i32>,

offset: u32,

}

struct BitAddress {

offset: u32,

mask: u32,

}

fn check_occupancy(coordinates: vec3<i32>, lod: u32) -> bool {

let lod_info = b_VoxelGrid.lods[lod];

// figure out where we are in a repeating world

let ramainder = coordinates % lod_info.dim;

let sanitized = ramainder + select(lod_info.dim, vec3<i32>(0), ramainder >= vec3<i32>(0));

// produce a bit index in the buffer

let addr = linearize(vec3<u32>(sanitized), lod_info);

return (b_VoxelGrid.occupancy[addr.offset] & addr.mask) != 0u;

}

Termination

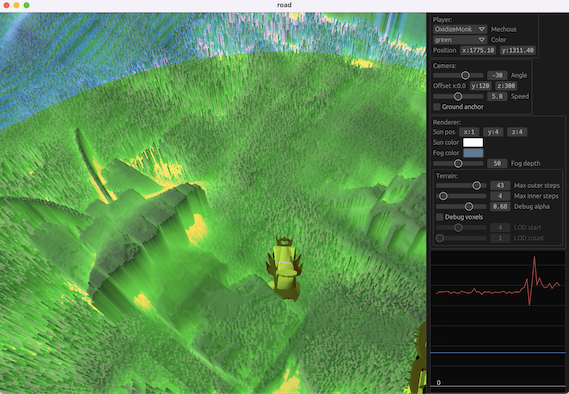

If we find a hit, we stop. But if we don’t find a hit, and keep going, how do we know when to stop? Our approach here is to limit the complexity. We configure limits on the number of voxels that can be skipped, as well as the number of fixed steps that can be taken. When any of these limits are reached, we just stop the ray and consider the terrain beneath it to be the collision result. Debug visualization shows such places in bright colors:

Analysis

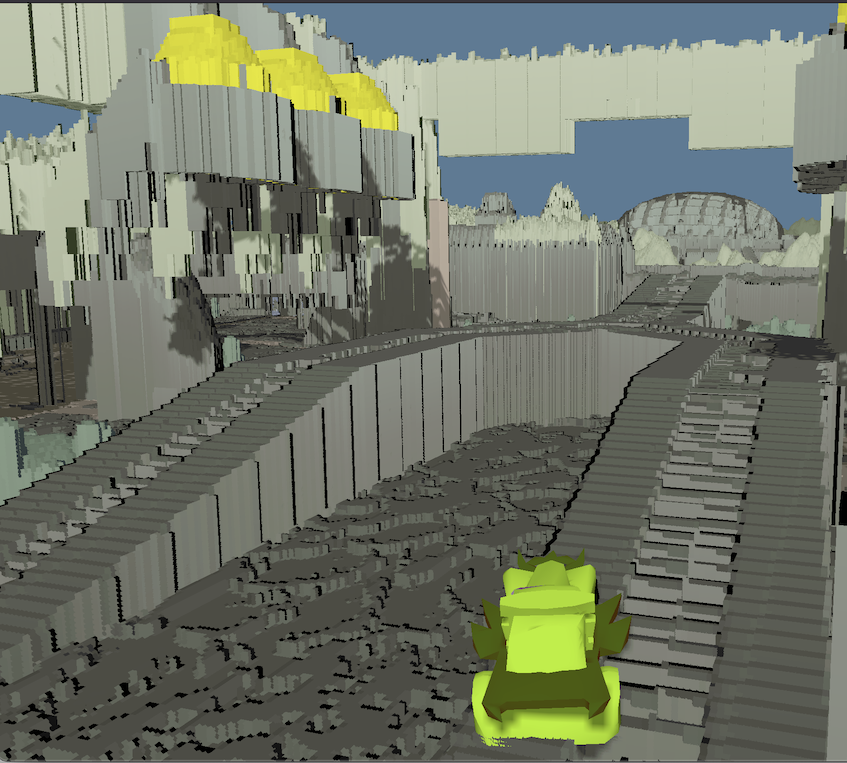

Generally, this algorithm reaches a sweet spot between quality and performance. It’s the most practical way to render Vangers game in full 3D from any point of view. It runs in real-time even on a mid-range system, and can run sufficiently well even on an old integrated GPU.

Issues

This method doesn’t quite require compute, but it does require storage buffers. So it can’t run on WebGL or older Android devices without some special care.

In terms of quality, there are spots with large terrain variation near the grid sides, which just sucks the rays in and rarely lets them pass. It’s unclear if there is an easy way out there. A heavyweight solution would be to adopt some sort of a Bounding Volume Hierarchy, where such complex places could be at least better isolated.

Future work

The Morton tiles have an interesting property that nearby voxels have neighboring bits, and we could potentially exploit this. For example, instead of checking a single bit at the beginning of the step, we could load all the 8 bits of the sub-voxels if we know they are together. This would have exactly the same cost as loading one bit, but would allow us to immediately know how to follow-up (skipping a step).

Another area of improvement is using this algorithm for shadows. The acceleration structure is view-independent, so there is a good opportunity here to benefit from code and data reuse.

Finally, now that we can truly look at front or even up, we need an environmental map for the sky.